As we all know, shoes are removed upon entering the Japanese home. Behind every front door, a small sunken patch of tile or exposed concrete, called a genkan, is dedicated to this ritual. This area is something between a porch and a glorified doormat, yet it occupies an integral place within the Japanese home.

The word “genkan” (玄関) literally means “dark and mysterious entrance”. It was inscribed above the entrance galleries serving early Zen Buddhist temples (perhaps a Zen monk’s idea of a pun) likening entering the temple to setting foot on the uncertain and tortuous path to enlightenment (or ‘gen’).

In the Edo period, the genkan was incorporated into secular life, but legislation restricted them to the homes of the elite warrior and priestly classes in which they served as a formal reception area. Important visitors would alight in the genkan and await a polite invitation to officially cross the threshold into a noble home by stepping onto the raised wooden floor (shikidai 式台).

By the Edo period , a genkan was incorporated into the homes of the lay classes. Though they may have been no more than a patch of bare earth within the typical farmhouse, the etiquette of entry was no less important. In traditional homes, sliding doors typically separate this small entryway from the private rooms of the home.

The genkan is still considered to be outside the home, serving as a place for visitors or callers to wait to be formally greeted in. To this day, it is customary for delivery people to step freely through the front door and into the genkan, but wait there to be ushered further inside.

In older homes, an alcove facing the genkan might have displayed, a cherished scroll, ikebana, or ceramics designed to leave a favorable impression on the waiting visitor. Today, it’s more typical for family photos to be put on show.

Thus, the genkan serves as a softer threshold where one might greet an unexpected visitor (and perhaps even offer them a cup of hot tea), but — in that so politely Japanese manner — decline to invite them in any further.

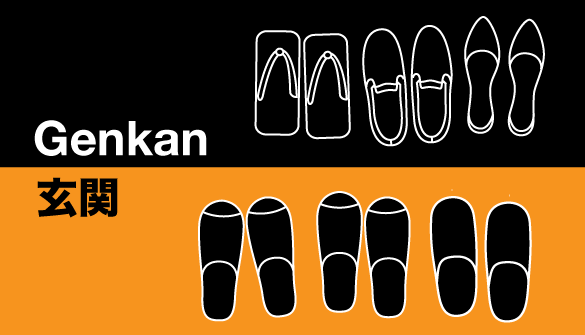

If one is lucky enough to be welcomed in, this is the place to remove shoes, don a pair of slippers and step into the home proper. It is a polite custom to bend down and turn the shoes so that they neatly face the door, ready to slipped back on when leaving. Alternatively, a shoe cupboard is usually adjacent for storing shoes out of sight. In public places (restaurants and bath houses for example) you will find small lockers. Each cubbyhole is locked with a wooden key.

Of course, the genkan would not exist were it not for the Japanese obsession with cleanliness. Removing shoes is designed to prevent dirt from entering the home and being tracked across delicate reed tatami mats. The Westerner must remember to avoid stepping into the genkan in socks or bare feet so as to not to bring dirt any into the rest of the house.

Traditional tatami floor mats are becoming less popular (and often absent altogether) in new homes where timber flooring has become the norm (hardly ever does one find carpet). Yet the ritual of removing shoes in the genkan remains sacred (if at times awkward) ritual.